Geddy Lee's Engaging Life and Memoir

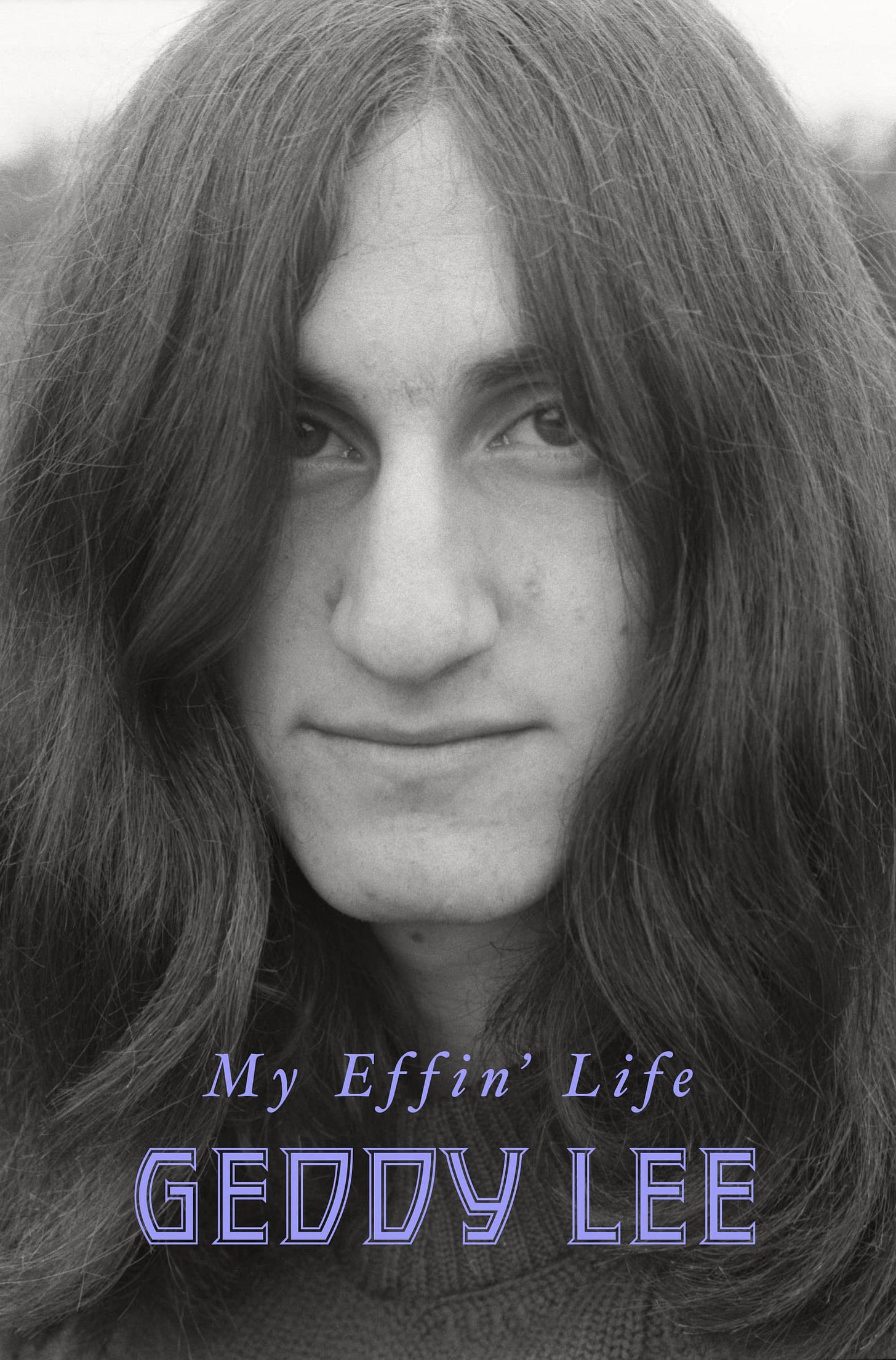

Review of "My Effin' Life" by Geddy Lee with Daniel Richler

The memoir, in general, is one of the more dubious of many dubious modern trends, but there are exceptions. One of them is Neil Peart’s inestimable, profound Ghost Rider: Travels on the Healing Road (Toronto: ECW Press, 2002). Peart’s bandmate Geddy Lee recently published another exceptional, at times astounding book, of interest even to those who are not fans but unquestionably required reading for those who are. (About the only aspect of the book that is underwhelming is its title.)

My Effin’ Life (New York: Harper, 2023) recounts any number of stranger-than-fiction stories. It has many parallels with Peart’s travelogue of grief and resilience, but it is not limited to one era of an indefatigable, amazing life but to Lee’s entire life (and that of his family). No matter how much of a Rush expert any given reader is, he will surely learn something about the band from the reading experience. But any reader will learn significantly more about myriad subjects while being riveted to a page turner.

What is difficult to read but ineffably more harrowing to have experienced is that Lee’s parents, Morris and Mary Weinrib, met in a Nazi concentration camp during the Second World War. Lee pieces together his family’s history and experience, from antisemitism to full-blown slave labor, warning that it is (of course) a shocking and arduous read, even suggesting that some may want to skip that particular chapter. Skipping it is not a reasonable option. Learning about the unprecedented atrocities of the twentieth century is necessary to understand how dire and inimical culture and politics had become by that point (and how to prevent it in the future), and Lee’s and Richler’s circumscribed and personal overview is a valuable primer in that regard. (They even cite and recommend further reading.) But learning about the tenacity, determination, and resilience of the Weinribs is even more important, as the basic decency and efficacy of most humans is incomparably more relevant than the subhuman behavior of some of history’s blackest villains and destroyers. It is sobering to contemplate that Lee (and Rush) likely would never have existed if the Nazis’ crimes hadn’t. One could perhaps conceive of a parallel universe in which they met anyway, but their defiant struggles and touching relationship, forged amidst inhuman suffering, deprivation, and evil, is a heroic, inspiring story all by itself. It is also a necessary reminder in trying, endarkened times of what is possible. Lee recounts his father’s efforts to find his mother after they were separated and their eventual settling in Toronto, where close family already resided. All of this—the romance, resilience, defiance, etc.—unquestionably inspired Lee’s life and work, resulting in some of the most exceptional, enlightened, humanistic music, lyrics, and performances of its modernistic, anti-human, dark time. Unfortunately, Morris Weinrib, his heart weakened by the forced labor in the camps, died of influenza at age forty-five. A twelve-year-old Gary Weinrib, suddenly the “man of the house”, mourned for a year, in accordance with the customs of Jewish culture.

This incalculable loss was the first of a series that continued for decades and is a theme of My Effin’ Life: dealing with the loss of those closest. But the book is primarily about life, not death, and Lee precedes to regale the reader with memories and observations of life after his father’s death, including becoming Geddy Lee; his embracing of his Jewish heritage while rejecting religion; his mother’s success as an independent entrepreneur; his courtship of Nancy Young (they have been married since 1976); and the history of Rush (and a lot more). Some of the people who are recounted (in words and images) include Rick Moranis, a childhood classmate of Lee’s; and lifelong friend Oscar Peterson, Jr., son of jazz pianist Oscar Peterson. Oscar Jr. is familiar to knowledgable fans, and Lee would eventually collaborate with Moranis on Bob and Doug McKenzie’s single “Take Off”, which remains the highest grossing and highest charting single (in the United States, anyway) in which Lee was involved. (Rush is technically a one-hit wonder in the United States.) But some of the most fascinating and informative stories involve his beloved bandmates Alex Lifeson, Neil Peart, and original drummer John Rutsey. Whether describing recording sessions or tour rehearsals or their lighter moments away from work, the reader will see priceless, previously unknown details of their working and personal lives (even private notes and E-mails) as well as the pioneering progressive rock they produced. Unfortunately, Mary Weinrib, Peterson, Rutsey, Peart, Peart’s wife Jackie, Peart’s daughter Selena, and many others who are remembered in My Effin’ Life are no longer living, and Lee’s accounts of how he dealt with these losses, as noted above, is a salient sub theme of the book. Peart’s grieving period following the deaths of his wife and daughter and his subsequent resolve to live intentionally and fully as much as possible while suffering from glioblastoma remind one of the Weinribs’ benevolent determination. Like so much of My Effin’ Life, the stories are inspiring.

Lee also writes candidly and frankly about regrets and mistakes. He takes himself to task for neglecting his wife and son for many years and for lack of communication with Lifeson during a period in which he felt marginalized in the band. Another sub theme of the book that can inspire any reader is self-improvement and the importance of nurturing relationships and communication.

Overall, Lee comes across as an honest, enlightened, diverse, well-rounded, and grounded citizen and thinker in an age in which too many people (especially prominent cultural people) are anything but. Rush generally projected themes of individualism, liberty, and life’s possibility (even amidst crushing injustice and tragedy), and while Peart wrote most of the lyrics, Lee sang them with conviction and passion. (A lyric from “Natural Science” inspired the title of this publication.) He generally extols those themes in his book, implicitly if not always explicitly. He even positively quotes Ayn Rand and addresses her influence on the band (more positively and graciously than I think Peart did in his later years). His views are not entirely consistent with individualism and liberty (such as his support for Canada’s “social safety net”) and he occasionally evinces incomplete understanding of Rand’s egoistic ethics, but he and his bandmates were and are rare public figures who espouse and embody individualism, egoism (properly understood), liberty, and human-centric ideas and themes during the decades when they were so poorly represented, and often denigrated, in the rest of the culture. Those themes, however implicitly, recur in the book and in Lee’s and Richler’s writing.

Another inestimable element of the book is its images. They are countless and fascinating, like the stories. Highlights include a snapshot of Lee’s and Young’s first kiss and Peart’s personal images snapped from his drum riser of bandmates and audience during the final moments of Rush’s final concert on August 1, 2015 at The Forum in Inglewood, California. (I was present on the floor and, however undetectable, am likely in one of the pictures somewhere.)

Just as no reader will come away from My Effin’ Life unenlightened, none will emerge uninformed. From Jewish rituals to Toronto geography to little-known details of recording and touring, virtually everyone will come away with increased general knowledge. (I found the details of co-producer Rupert Hine’s vocal coaching in 1989 and 1991 particularly noteworthy. Unfortunately, Hine is another departed collaborator whose passing Lee mourns.)

The book’s few shortcomings are trivial. There are a few factual errors, but they are well below the average of typical memoirs. A table of contents would have been useful, too. But those are cavils in this context.

My Effin’ Life is recommended to a degree to anyone who likes to read, but it is required reading for anyone with even a passing interest in its author. It is the latest work in a remarkable (and remarkably productive) life, full of fascinating details and anecdotes of that work (including Lee’s solo album My Favorite Headache) that deserve more attention than space provides. Re-reading it is also advised; it is a treasure trove of information on some of the greatest cultural works of our lifetimes, and a lot more.