“What have we become?

“Just look what we have done.

“All that we destroyed, you must build again.”

White Lion, “When the Children Cry”, written by Vito Bratta and Mike Tramp, 1987

“… I can’t describe White Lion. We are thrash metal to my grandma, and … to thrash people, we are Julio Iglesias. Someone told me we are playing rock and roll music; I say, ’That’s fine with me.’” Mike Tramp, in White Lion, Escape from Brooklyn (home video), 1992 (recorded circa 1991)

Note: Those of a Mark Steyn/Robert Tracinski viewpoint, which I will explain shortly, will find nothing of interest here (unless I can inspire you to change your mind). The viewpoint in particular is the one that virtually all music from The Benny Goodman Quintet (before Charlie Christian and his ringing, novel electric guitar made it a Sextet) through Miles Davis, “California Girls” (The Beach Boys), and “California Gurls” (Katy Perry) is nothing but “pop music”, more or less equally uninteresting, meaningless, and certainly unworthy of a “thinkpiece” or any elucidation or explication. My view is different. “California Girls” is closer to Camille Saint-Saëns to “California Gurls”, and “When the Children Cry”, quoted above, evolved out of a classical guitar piece Bratta was working on (classical is the primary genre Bratta plays now). Feel free to skip this and return when I explicate John Dewey the mind vitiator again or decide to write about La Traviata and its possible connection to Queensrÿche’s Operation: Mindcrime (never mind—we’d be back to a piece like this).

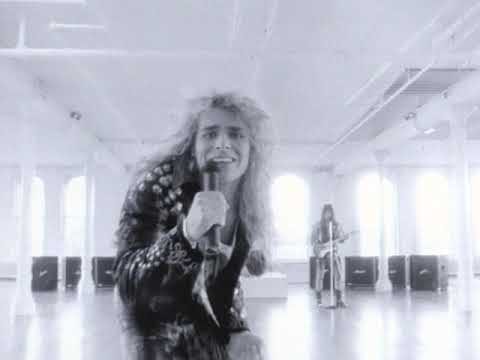

In 1979, an eighteen-year-old Dane named Michael Trempenau emigrated to the City of New York. Around three years later, Mike Tramp (as he would become known professionally) met Vito Bratta, a guitar virtuoso his age from Staten Island, at L’Amour, a Brooklyn club. The two quickly formed a songwriting partnership that, after years of growth and false starts, would lead to a deal with Atlantic Records, an album certified multi-platinum by the Recording Industry Association of America, an RIAA gold album, a #3 hit on “The Billboard Hot 100”, other hits, MTV airplay, and a robust fanbase … before suddenly imploding in the waning months of 1991.

White Lion, the result of their eight-year persistence, is mostly forgotten now outside that fanbase, but some of the songs they wrote are as empowering as ever—and indubitably more relevant than ever. (“It just keeps re-relevanting itself,” as Steven Schub, who is now my friend, introduced one of his band’s songs in 2002 during a live recording session in New York.) The band’s four studio albums, particularly the three with Atlantic, are stellar collections of idealism, classical liberalism, and value-oriented romanticism stylized in song, exceptionally executed with warmth and élan.

The pair that founded and steered White Lion throughout its existence was a somewhat odd couple. Tramp has commented that he had some trouble communicating with the reticent Bratta, and interview video footage documents two strikingly different personalities. Bratta loved Van Halen (he would eventually befriend Edward) and other rock and blues guitarists; Tramp’s diverse influences included Queen and the egregiously underrated Thin Lizzy (Tramp later listened to Thin Lizzy’s “Southbound” for inspiration just prior to going onstage every night). Quickly finding a management team interested in their potential, the team exhorted the artists to write a song. The first song was “Broken Heart”, which the band would later re-record to better effect and affect on their final album. In the meantime, they continued to write songs, settling for a time with bass guitarist/keyboardist Felix Robinson and drummer Nicky Capozzi, both of whom helped write some of the early songs.

It was the Eighties, of course, and one of the many melodic genres saturating the airwaves and automotive speakers in that decade was metal/hard rock. This genre, in general, had the best musicianship in popular music since jazz. By the Eighties, metal, while retaining and improving a commitment to musicianship, no longer shared improvisational tendencies with jazz (early metal did). For better or worse, White Lion were closer to “hard rock” than “heavy metal”, and they more or less followed that strictured, less extemporaneous trend in heavy rock bands at that time. Sartorially, they were essentially a “hair band” from the get go, but, like others from the US East Coast, they were grittier, more serious, and more skillful than their West Coast counterparts. From their earliest songs, including “El Salvador”, “All the Fallen Men”, and “Cherokee”, Tramp’s lyrics were more serious and pensive than much of the sleaze rock of the Sunset Strip, and Bratta’s unique sweep picking and eight-finger tapping distinguished him from his peers, who needed session players to “ghost” for them in the studio.

1983 was the first year that a metal/hard rock album topped “The Billboard 200”, and the modish music industry was keen to sign such bands. Elektra Records soon optioned White Lion for an album deal, leading to recording sessions in early 1984 in Frankfurt, West Germany with Peter Hauke producing. Elektra rejected the resulting album (understandably, as it is by far the band’s weakest—even the original “Broken Heart” is a shadow of its remake), but the band and management persisted, shopping the completed album to other labels and going through rhythm section members, including future Black Sabbath bassist Dave Spitz, brother of Anthrax guitarist Dan Spitz.

By 1986, White Lion found bassist James LoMenzo and drummer Greg D’Angelo (original drummer of Anthrax, suggesting how small New York music circles were). This tight, disciplined lineup remained for most of the rest of the band’s too-short, whirlwind career.

Later that year, the band signed a deal with Philadelphia indie label Grand Slamm Records, who agreed to release Fight to Survive, the album recorded with Robinson and Capozzi two years earlier. Grand Slamm folded shortly after the album’s release, and the album would become a collector’s item of sorts for a long time. It is by no means unlistenable, but it shows the growing pains of a growing band, is very much a time capsule, is significantly inferior to what was to come in both songwriting and production, and is generally for completists—though it is certainly a harbinger of future glories beyond the inclusion of the original “Broken Heart”. The production, like that of the second Yes album, is grating on this listener—but the songs and musicianship, as on that second Yes album, redeem it to a degree.

Whether or not Fight to Survive helped, White Lion and Loud and Proud Management (the aforementioned team) attracted the attention of Atlantic Records. Contracts were signed, and in 1987, the band recorded Pride, their Atlantic debut, with Michael Wagener, a star producer for that genre.

Pride is an arrival, less of a totem or period piece than many of their peers’ albums of that era. Bratta and Tramp wrote all the songs (the longtime rhythm section would never contribute to songwriting). It starts conventionally enough with “Hungry”, one of the few occasions Tramp wrote a stereotypical “cock rock” lyric, but musically it betrays the band’s grittier New York roots. By “Lonely Nights”, the second song, a more somber, contemplative tone is established, with empathetic lyrics. Bratta’s fast riffing on “Lady of the Valley” is closer to the “heavy metal” under which the Columbia House record club would later file the band. Wagener tacks a lengthy singalong intro to “All You Need is Rock ’N’ Roll” which includes a “Be-Bop-a-Lula” reference, a hint at the band’s awareness of roots deeper than metal/hard rock.

Wagener blends acoustic and electric guitars adroitly in “Wait”, the band’s emotive breakthrough hit. After Tramp returned from a visit to his native Denmark after Christmas in 1985, Bratta played him his latest songwriting project. Tramp spontaneously sang, “Wait, wait, I never had a chance to love you.” Eventually, the song peaked at #8 on the pop charts. It’s a more sentimental, serious tune than some of its company and likely wouldn’t appeal to the cynics and snark mongers that became commonplace in more recent decades (and I like some of the latter). “Tell Me”, a minor hit, is a touching teenage love story song with an infectious melody—the band has an undeniable pop sensibility underneath the crunch of Bratta’s guitar and honed precision of all the players.

The album closes with a paradox titled “When the Children Cry”. It is their most famous song and perhaps their most atypical. LoMenzo doesn’t play on it and, excepting light auxiliary percussion, neither does D’Angelo. It is defined by Bratta’s cascading acoustic guitar. (It started as a classical guitar piece, but he plays a steel-stringed guitar, not a nylon-stringed guitar, here.) This song sort of cemented Tramp’s reputation as the Bono of hair band frontmen, a humorless, starry-eyed idealist with a bleeding heart. The caricature is unfair to both. My uncle, a Baby Boomer with no particular affinity for this genre, was so impressed he opined it was as good as a Beatles song. It has some commonalities with “Imagine” even though it is incomparably better, lyrically and musically (a low bar to clear)—and more religious (or at least “spiritual”). Tramp drew lyrical inspiration from watching Live Aid in 1985. Vocally, his baritone rasp here sounds more like one of the better modern hipsters, such as the singer of The Lumineers, than Cinderella’s Tom Keifer. Conservatives were particularly dismayed by lyrics, during Reagan’s second term no less, such as: “No more presidents, and all the wars will end—one united world, under God.” Whatever one thinks of some of the concrete political or “spiritual” ideas expressed in the song, it is a prescient observation, ahead of its time, more relevant than ever, noting generational decline and destruction that is bipartisan and transcends politics. (Many modern listeners, conservative and otherwise, don’t know how to evaluate cultural works by considering essentials, missing deeper points while being hung up on lesser concrete lines. Notably, my atheistic anarcho-capitalist friend and writer Billy Beck, who was a lighting director for part of the Pride Tour in 1987, has never expressed any disdain for any of Tramp’s lyrics, even the vaguely “liberal”, one-world, “Kumbaya” lines of “When the Children Cry” and the lyrically similar “All Join Our Hands”. He recently told me, “Mike was a really nice guy.” You should hear—and read—Billy’s ire for “commies” and “liberals”.)

Pride would sell millions of copies in the United States alone. It is by far their most successful album while being the weakest, artistically, of the Atlantic albums. Tramp occasionally lapses into lyrical cliché, and Bratta’s style, while already unique, draws inescapable comparisons to Edward Van Halen. Tramp and Bratta even resembled Roth and Van Halen, but the band’s defining timbre and temperament were generally closer to the more serious and philosophical Sammy Hagar era. Flaws aside, listening today is like finding an oasis of melody, instrumental skill, and value orientation in the aesthetic desert that is the twenty-first century. The title of the album is an obvious reference to lions, but the band sounds proud and dignified, unlike some of their whimpering, shoe-gazing predecessors—exemplars of what Aristotle called the crown of the virtues.

The band embarked on a long tour, opening for the likes of KISS, Frehley’s Comet (with former KISS guitarist Ace Frehley), Ozzy Osbourne, Aerosmith, and AC/DC while headlining smaller venues. In February 1988, the band played a series of sets at home at The Ritz, which MTV videotaped and broadcast a few months later. The audio recordings would eventually be released on archival releases and compilations. Tramp struggles a bit vocally, but the recordings reveal a complicated band with lighter moments: During band introductions, Tramp introduces Bratta as “the Italian Stallion”, and someone offscreen (probably LoMenzo) introduces Tramp as “New York’s favorite Danish [sic]”. The live arrangement of “When the Children Cry” included the rhythm section joining at the start of the guitar solo (LoMenzo’s lines integrate well with D’Angelo’s precise internal metronome.)

Eventually, in early 1989, White Lion returned to New York from a too-long tour to follow up their breakthrough. Two years was an eternity in the 1980s, especially for a band with one near-blockbuster album, and the lost momentum probably led to their commercial decline.

There would be no aesthetic decline—just a commercial free fall.

To be continued …