[Note: This post is too long for the E-mail feature. Please click through or view on Substack for the full article.]

“I have lived in one house in Baltimore for nearly forty-five years. It has changed in that time, as I have—but somehow it still remains the same. No conceivable decorator's masterpiece could give me the same ease. It is as much a part of me as my two hands. If I had to leave it I'd be as certainly crippled as if I lost a leg.”

H.L. Mencken, cited at menckenhouse.org

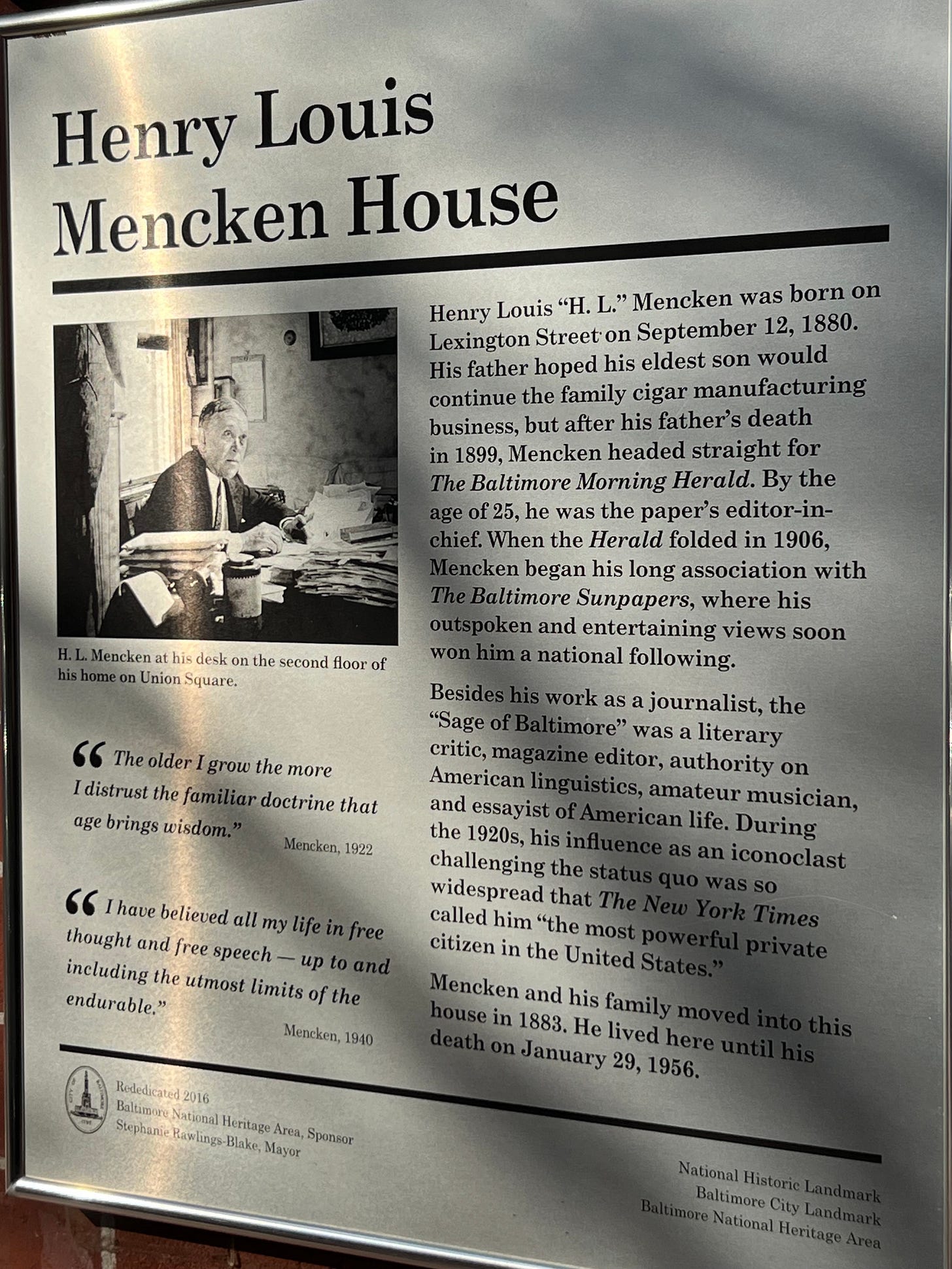

In October 1883, prosperous Baltimore cigar factory proprietor August Mencken purchased a long, narrow row house at 1524 Hollins Street in Baltimore for $2,900. It is across the street from Baltimore’s Union Square Park. He moved into the home with his wife Anna and three-year-old son Henry Louis (already known to family as Harry).

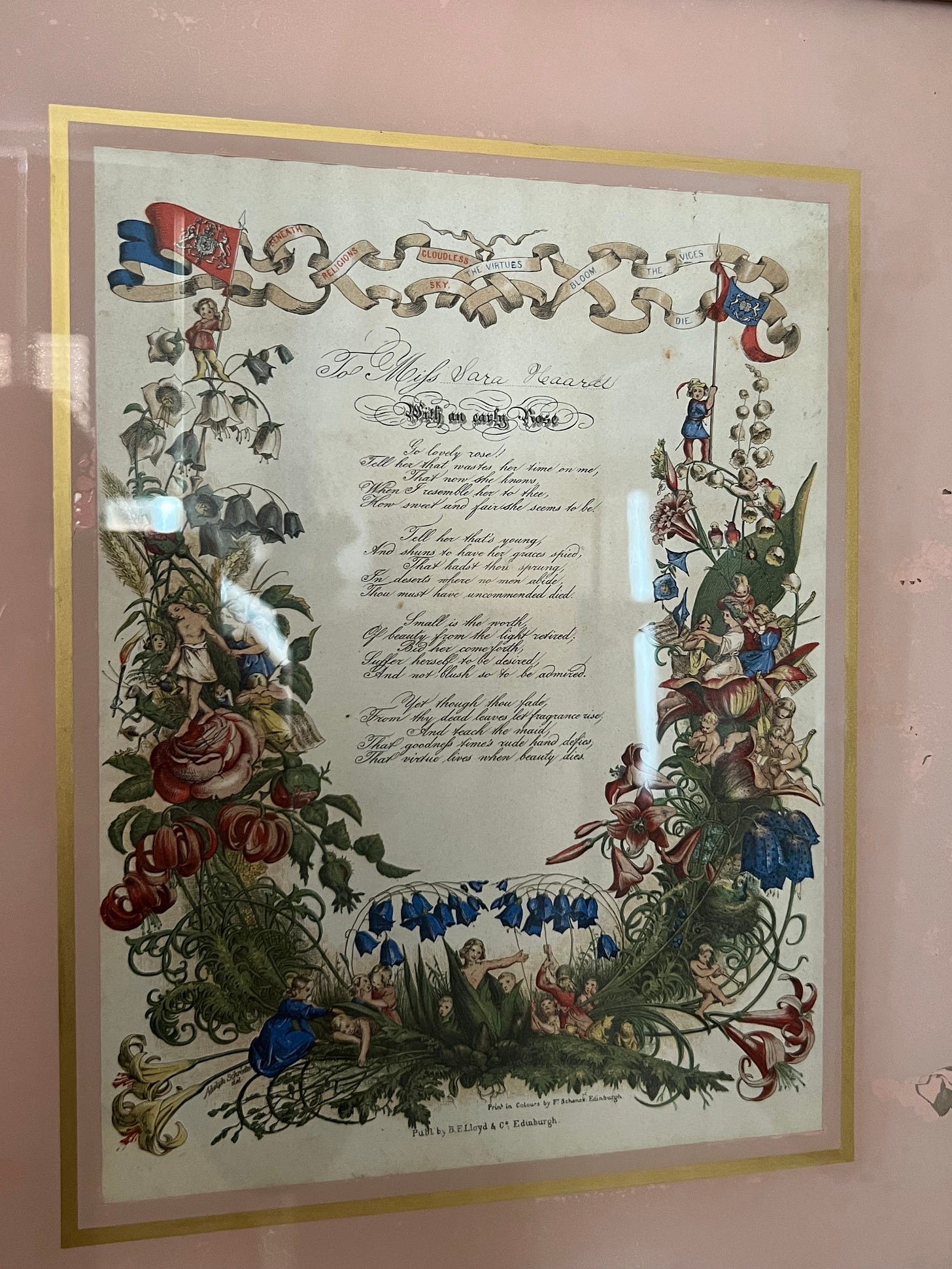

Harry would become prolific writer and cultural critic H.L. Mencken, who started as an eighteen-year-old Baltimore newspaper reporter and became known throughout America and beyond as “the Sage of Baltimore” and “the American Nietzsche”. While one of his first published books was indeed The Philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche (1907), he wrote volumes of material, serious and satirical, on plays, novels, philosophy, history, politics, and beyond. And, apart from five years when he lived with wife Sara Haardt in an apartment on Cathedral Street in Baltimore, he spent the rest of his life residing at 1524.

Despite (or because?) of a rugged persona, satirizing and objurgating what he regarded as cultural and political “frauds” and “mountebanks”, Mencken was a homebody and has even been described by at least one biographer (Terry Teachout, I think) as a “mama’s boy”. Hollins Street was the center of his universe for decades. He discovered beloved literature at a neighborhood library as a boy and received his first printing press as a Christmas gift in 1888. As an adult, he declined to move to New York, which he disliked, and opted to stay in a hotel Monday through Thursday evenings and return to Baltimore by train Friday afternoon during long periods of work there. He traveled the world, for work and leisure, from Europe to the Caribbean to what is now Israel. His estimation of many of these places was similar to his estimation of New York and the frauds and quacks he lampooned and denounced in academia, politics, Broadway, Hollywood, etc. (E.g., Los Angeles was “the authentic rectum of civilization”; the Arkansas legislature passed a resolution praying for his soul after he referred to the state as “the apex of moronia”. And he certainly wasn’t impressed with the Gaza Strip.) He never stopped returning to Hollins Street, where he wrote much of his multi-volume corpus and became, according to The New York Times, the most powerful private citizen in America. While Mencken did have a reputation for objurgation and ridicule, there were many things he championed, including logic, truth, and liberty. His long-time family home was evidently just as important to him.

Mencken died at 1524 Hollins Street in the early morning hours of January 29, 1956 at the age of seventy-five. His younger brother, August Jr. (Gus), continued to reside there until his death in 1967. August Mencken, Jr. bequeathed the house to the University of Maryland. It was left as it was but slowly deteriorated for decades. Years ago, Max Edwin Hency, a retired naval officer and Mencken Society member, donated $3,000,000 for its restoration, and it reopened for tours and events in late 2019.

Yesterday, Jim Kennedy of The Society to Preserve H.L. Mencken’s Legacy showed me the legendary house, which Mencken wrote about extensively in his celebrated books Happy Days, Heathen Days, and Newspaper Days.

Upon entering the front door, one can see Mencken’s music room on the left. His piano is there, purchased by his father when he was a boy, as well as the coat of arms of the Saturday Night Club, a group of amateur and professional musicians, including Mencken, who gathered in the house on Saturdays to play music.

As one continues into the first floor, behind the music room and to the left of the corridor along the right side of the house, a receiving room remains. This was originally a dining room, but Mencken decided to move the dining room behind it because he preferred to receive guests in this room.

Behind the receiving room, the dining room has been converted into an ADA compliant bathroom and a small kitchenette and storage space. Behind that is a small backyard area where the Mencken family kept a pony for Harry when he was a boy. One can also see Mencken’s dog’s grave and other fascinating sights.

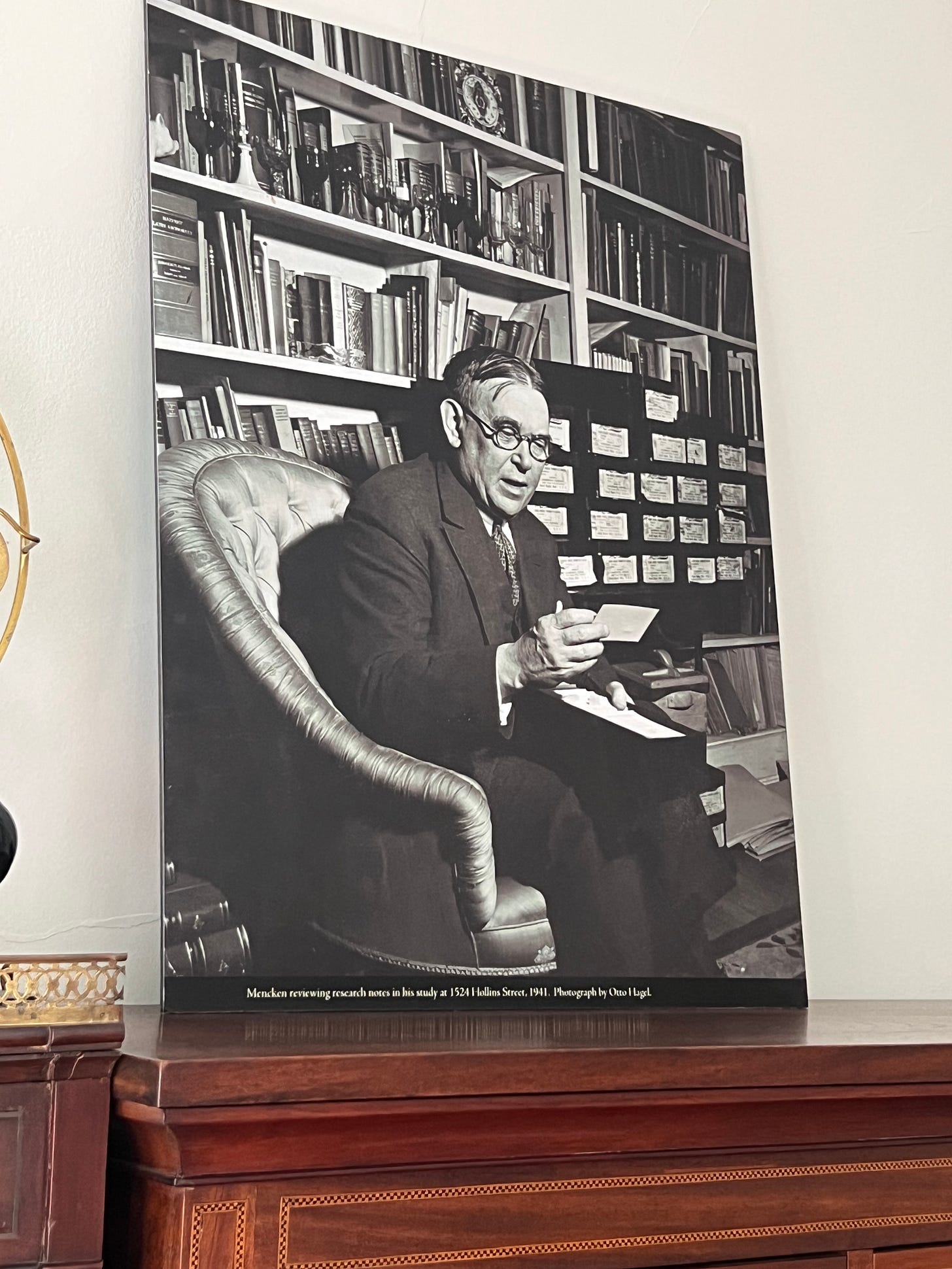

The tour continued onto the second floor of the house: Mencken’s large home office.

The third floor is not generally open to the public. Its bedrooms have been converted into nondescript offices, and The Society frequently broadcasts “Mencken Minutes”, informative short video discussions, from there. I was able to see the exterior of Mencken’s bedroom, however.

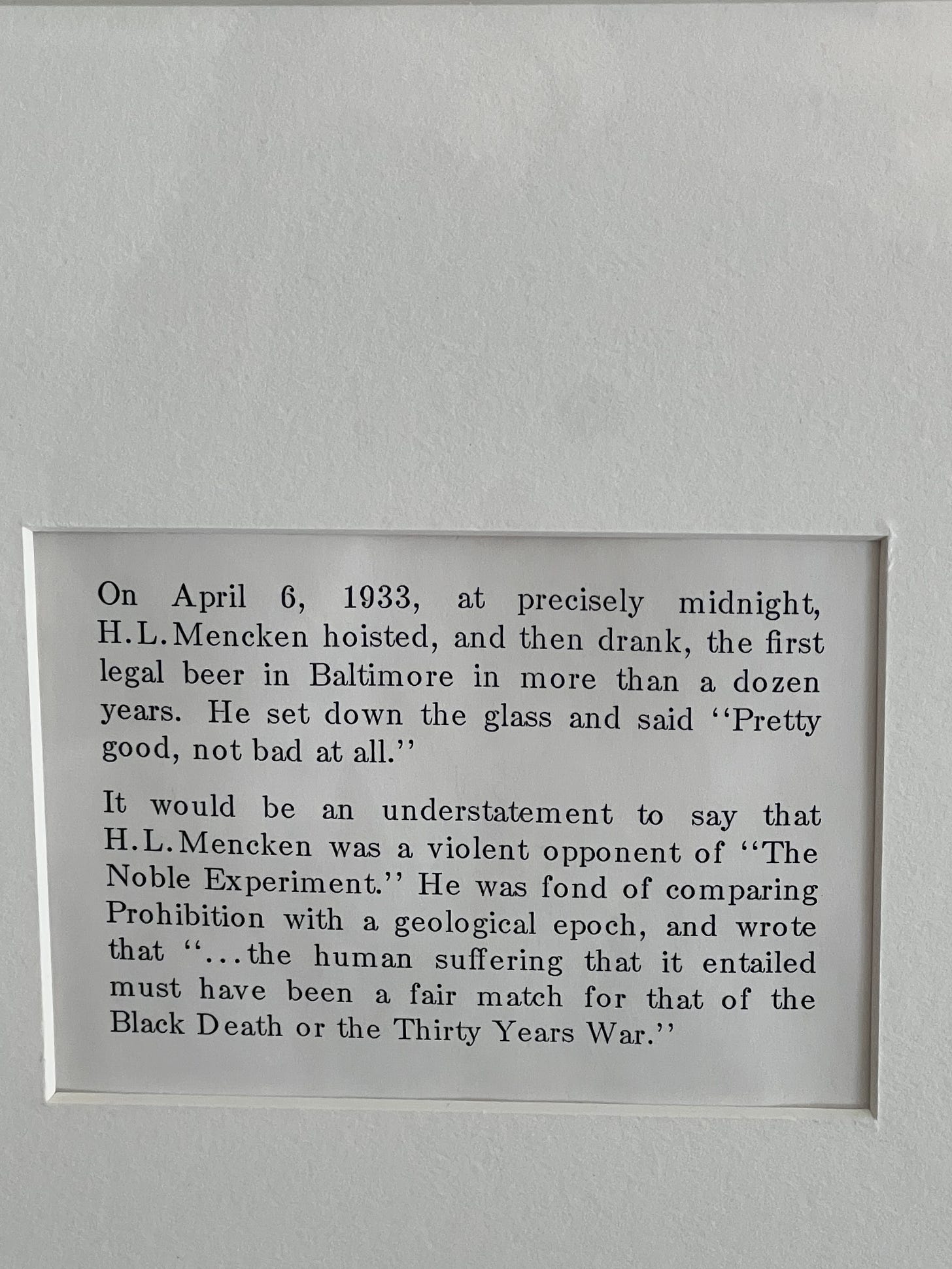

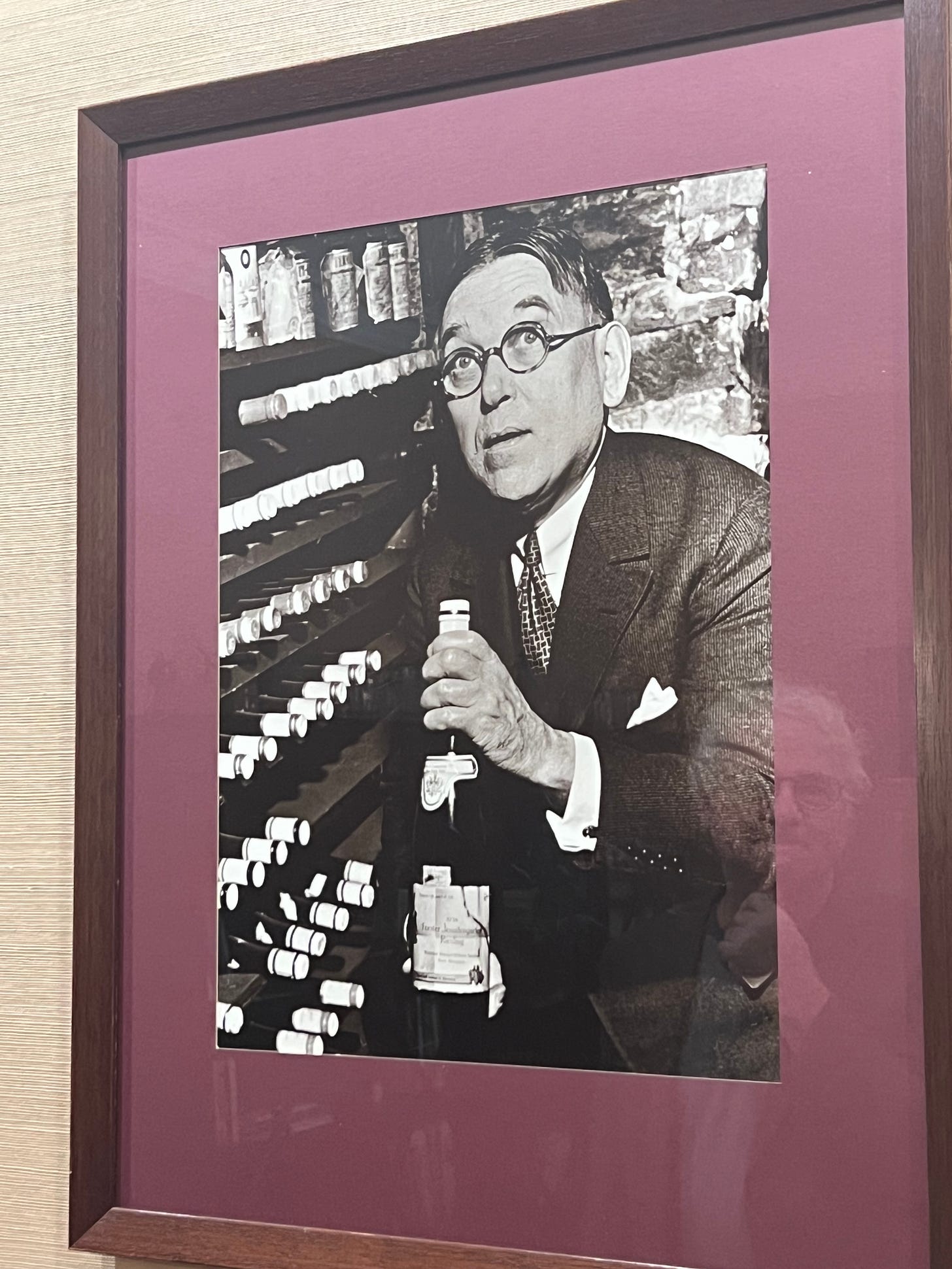

Many compelling placards, artifacts, and photographs, some famous and some not, adorn the walls and furniture of the house. Some are below.

The Society to Preserve H.L. Mencken’s Legacy should be commended for restoring the house and keeping that legacy alive. The experience would be fuller and more reflective of Mencken and his spirit if it included more of Mencken’s iconoclasm and courage. There are hints of it in the placards and captions, but I think the house’s caretakers tend to downplay the controversy and foursquare intransigence that contributed so much to that legacy. The self-described “extreme libertarian” received so much “hate mail” as a young man it filled at least one filing cabinet, prompting his mother to exclaim, “Harry, what are you doing?!” One wouldn’t know from the tour that he was a writer who made influences like Mark Twain and Robert Ingersoll (an orator, not a writer) seem as innocuous and winsome as Beverly Cleary and Norman Vincent Peale by comparison. Also, one hopes that they can raise enough money to start a small gift shop. His writings are not available for sale in the house. Nonetheless, the Society is doing the vestiges of culture, which Mencken noted were starting to decline even then, an invaluable service.

Also of interest:

The sole known extant recording of Mencken’s voice is a lengthy interview during which he speaks at length, inter alia, about the house (pictured).

My review of a collection of some of Mencken’s early newspaper columns, published at The Objective Standard.

"September 12 is Most Endangered Species Day"

September 12 is Most Endangered Species Day

"I believe that liberty is the only genuinely valuable thing that men have invented, at least in the field of government, in a thousand years. I believe that it is better to be free than to be not free, even when the former is dangerous and the latter safe. I believe that the finest qualities of man can flourish only in free air – that progress made und…