“More than anything, Van Halen was my dad’s name. And though I never would have said this at the time, when I think about it now, it was in many ways my dad’s band. Ed was asked by a journalist once what inspired him to play music. ‘My dad,’ he replied. ‘He was a soulful guy.’

“All the lessons our father taught us about music, energy, showmanship, and professionalism are what would eventually turn this bunch of teenagers in a basement in Pasadena into the biggest band in the world.”

Van Halen, Alex. Brothers. New York: Harper, 2024, p. 62.

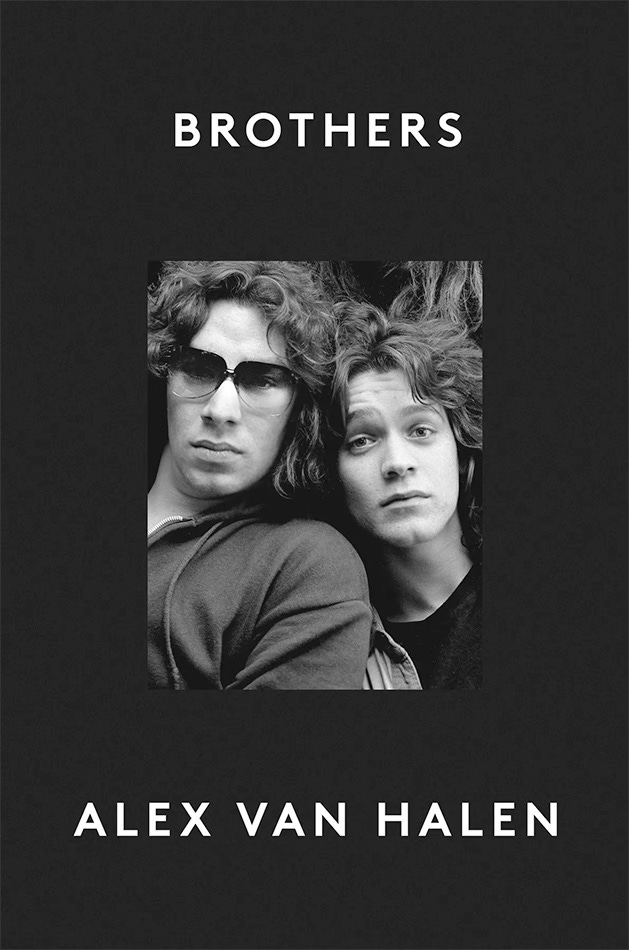

World-renowned, iconic drummer Alex Van Halen has published Brothers (Harper), a slim volume that is many things. It is part of his ongoing grieving process four years after the death of his younger brother; it is a tribute to his late parents; it is a detail-oriented memoir of his, his brother’s, and his band’s first few decades; and it is a compelling reading experience, especially for fans of Van Halen or enthusiasts of the final period of exciting popular music and culture.

As its title suggests, it is not an autobiography like Geddy Lee’s recent, much more substantial My Effin’ Life (also published by Harper, last year). The titles practically speak for themselves. Van Halen’s book has a narrower scope that even its title doesn’t entirely reveal.

Van Halen received literary help from Ariel Levy. (There is an irony here. Levy is the author of Female Chauvinist Pigs: Women and the Rise of Raunch Culture. I don’t see why the Levy of the time wouldn’t consider a female Van Halen fan enjoying, inter alia, “Hot for Teacher”, “Good Enough”, and “Poundcake” a “female chauvinist pig”. Just watch the music video for “Poundcake”.) Brothers is an intentionally easy read, “conversational” and intimate, covering all aspects of the life and work of the brothers Van Halen from the author’s earliest memories in their native Netherlands in the mid-1950s to around 1985, when the first version of their band broke up as David Lee Roth departed. That was certainly not the end of the band or the brothers’ personal or professional relationship, which continued until Edward’s death in 2020.

Sammy Hagar, Van Halen’s second vocalist, publicly complained that he’s not mentioned in the book. That’s not quite true; he’s mentioned twice in passing. (As the drummer recounts, producer Ted Templeman, who signed the band to Warner Bros., thought he should replace David Lee Roth. In 1977.) That’s two more references than third vocalist Gary Cherone. The author’s first two wives aren’t even mentioned by name (and the marriages occurred during the years covered by the narrative). The book is dedicated to Stine Van Halen, the author’s third wife, whom he praises for helping him with addiction and grief. But the author barely mentions his sons.

So this is a fragmented account. Whether or not that is a judicious decision on the author’s part, it’s the decision he made. Fans of Van Halen’s Sammy Hagar era—which is when this writer became interested in the band—may be disappointed, not only at its absence from the book but by the implication the author isn’t interested in it anymore. (He obviously considers the Roth era in a class by itself.) The book is also a discursive account. Van Halen will occasionally tell stories out of chronological order, e.g., when he jumps from the 1982 album Diver Down straight to his father’s death before covering the monumental events (and albums) that occurred in between. Jan Van Halen died four years after Diver Down (and they were eventful years to say the least).

There may be legitimate criticisms of Brothers, but they are less important than what the reader will learn and experience during the relatively short read. Vivid memories covered include the family’s journey by sea to the United States, including the brothers playing music for fellow shipmates and the elder van Halen boy (the capital V would come shortly) taking interest in a girl on the ship who departed from the voyage prematurely. The drummer remembers his musician father’s stories of being forced to play for Nazis when his native country was occupied during the Second World War. He recalls his mother Wilhelmina’s exhortations to her sons to be respectable in their new country and always wear suits (long after they had no professional reason to wear them). Jan Van Halen, a woodwind player, labored long and hard on his woody clarinet sound, which inspired his sons during their years of tinkering with their famous “brown sound” (as they referred to it, with Edward’s unique guitar tone). Some particularly gruesome passages recount Jan’s and Alex’s horrific hand injuries. The father lost part of his finger (surely even more horrific for a wind player than for most people), and the son almost lost a finger in an industrial accident in his teens. Both injuries affected the players’ respective techniques, and Alex’s altered the sound of his drumming. This would endear him, years later, to touring partner Tony Iommi of Black Sabbath, whose playing and sound was altered by losing two fingertips on his fretting hand in a similar industrial accident. Brothers could just as accurately be titled Family.

Ozzy Osbourne (and many others) have commented on the type of personality required to bang on drums for a living, and Alex Van Halen fits the stereotype (and yes, there are entertaining Osbourne stories and other tales of road hi jinks in Brothers, too). The elder brother, who was determined to be “gifted” at school in Pasadena, nevertheless earned a reputation for brashness and aversion to authority. He had an insouciance his sensitive brother, who took things exceptionally personally, didn’t have. Alex remembers how dogs “hated” his brother and would attack him due to the extreme vulnerability he exuded. These kinds of details ensure Brothers is required reading for all Van Halen fans.

There are equally illuminating details of their other “family”, the band, as Alex Van Halen remembers the Van Halens, David Lee Roth, and Michael Anthony toiling around southern California for years before finally being discovered by Templeman in 1977. There are details of recording sessions, from prehistoric sessions in Roth’s parents’ bedroom. There is the infamous 1976 demonstration recording produced by Gene Simmons when they were still struggling. Later, the author describes Templeman-helmed sessions for Warner Bros. which included considerable strife between the producer and guitarist. The drummer remembered the battles with a certain empathy, noting the record label pressured Templeman to sell records, and Edward’s madcap artistic muse sometimes made that something of a challenge. Alex remembers other compromises, including those involving album cover artwork, that were inherent in mass entertainment commerce in the late twentieth century. Enthusiasts will appreciate details of which guitar solos were overdubbed and which were recorded “live in the studio” as well as tidbits of ambient sounds (including car horns and engines) in Van Halen’s and Templeman’s innovative recordings. There are photographs from the author’s personal collection that help reify some of these stories visually.

Edward and Alex Van Halen decided early on they would not collaborate with other artists. Edward eventually changed his mind, producing Dweezil Zappa’s debut single and, more famously, playing the guitar solo for producer Quincy Jones on Michael Jackson’s “Beat It”. According to Alex, Edward’s contribution to “Beat It” was far more than his guitar solo, as he rearranged the track substantially without credit or compensation. Alex was against all of it despite his appreciation of Dweezil’s father, whose Utility Muffin Research Kitchen home studio inspired Edward’s famous 5150. And he’s still a little upset that Thriller kept Van Halen’s 1984 out of the number one slot of “The Billboard 200”. (There are “first world problems”, and there are “rock star problems”.)

Brothers is a story of artists and entertainers who flourished when the two weren’t mutually exclusive. Its author remembers outperforming most of his American-born classmates, and he credits the continent of his birth. He’s right. Europe was not only the land of philosophy and art, but its schools were not infected with John Dewey’s mind-vitiating Progressive education to the degree American schools were, with results gradually, then suddenly, worsening across the decades. Van Halen, a unique band, synthesized the best of both of their homes. Their artistic, European side can be heard in Edward’s virtuosity, the classical influence, and the band’s complex arrangements. Their entertaining, American side can be heard in catchy, exuberant pop melodies; Edward’s technologically innovative sounds; and Roth’s and Hagar’s usually optimistic, often proud lyrics and stage presence. Considering culture’s decline since the decades covered by Brothers, including the lachrymose shoe-gazing of the worst of grunge and the mind-numbingly simple repetition of post-Eighties popular music, one could consider Baby Boomers on both sides of the Atlantic as the last generation to produce large quantities of decent, inventive popular culture. The decline in education and the decline in culture are interrelated. Brothers is not exceptionally erudite, and it isn’t supposed to be, but its author does come across as smarter than the average celebrity (especially among the younger generations). They were a sophisticated musical expression of pure joy (not the phony joy of certain ersatz recent cultural and political mountebanks), and only a musical family of Euro-American Baby Boomers could have produced the phenomenon that was Van Halen.

Brothers is also a story of paradoxes. Chuck Klosterman has noted the paradoxes of Van Halen in his track-by-track ranking of their catalog: “Van Halen is, in many ways, the high-profile exception to otherwise inflexible rules: classically trained virtuosos who make music for getting hammered in parking lots. A metal band that rarely plays metal. A legendary live act consistently criticized for their terrible live performances. A caricature of leering masculinity that proved unusually inclusive to female audiences. An embodiment of American exceptionalism, spearheaded by two Dutch Indo immigrants [Wilhelmina Van Halen was from Indonesia] who could barely speak English when they arrived in Pasadena. There are simply no other bands like this. They were copied constantly and no one ever got it right.” (The author expresses particular irritation and bemusement at the band’s legions of Eighties imitators, though he is unfair to White Lion, who were exceptional and singular.) The brothers themselves were paradoxes. Edward’s loud, proud, confident, bold musicianship was the ultimate outlet of a truly brave artist who was nonetheless so sensitive and reticent he was known to tear up, and he evinced such uneasiness dogs reacted to it.. Alex the puissant drummer, the puckish scourge of Pasadena teachers and other authority, who set tires on fire and trashed hotels on the road, reveals his own sensitive, sentimental, even romantic side throughout his book. Read it for some of the lurid, some of the filial, and even many ironic, details.

Now a septuagenarian, Alex Van Halen has reportedly retired. Regardless of what he left out, Brothers, the story he chose to tell, would be a worthy last work. If that is in fact what it is, his retirement is well earned.